"If his Majesty will, during their absence, assume the counties into his possession, divide the lands among the inhabitants...and will bestow the rest upon servitors and men of worth here, and withal bring in colonies of civil people of England and Scotland...the country will ever after be happily settled".

In this letter to James I Sir Arthur Chichester was expressing the sentiments that would lead to plantation. With the Flight of the Earls of 1607 the way had been made clear for England to extend its jurisdiction into the previously Gaelic stronghold of Ulster. A Royal Inquisition was founded in 1609 to distinguish between Crown and Ecclesiastical land. Armagh was calculated to contain 81,160 acres of land of which 42,000 acres was to be set aside for plantation. The settlement, it was hoped, would not only finally establish English authority in Ulster but also destroy the Gaelic social structures that had proved so detrimental to English ambition in previous centuries.

In 1610, Henry Acheson of Edinburgh was granted 1,000 acres of land here. He constructed a bawn measuring 140 feet x 80 feet with four towers. As a condition of settlement, he brought with him nineteen Scottish families to farm the land and to form the nucleus of the community. Sir James Douglas also received 2,000 acres of land at Cloncarney but soon sold his grant to Henry Acheson, acting on behalf of his brother Archibald. Even before 1628 when Archibald's title to Henry's manor was ratified, Archibald seems to have taken control of Henry's estate sometime in 1614: letters of title granted to Archibald in 1628 over both manors seem to recognise and ratify the earlier title to him over both manors in 1614. As well as estates in Armagh, the brothers were granted estates in Cavan and Longford and probably maintained Scottish estates also, making their movements and actions difficult to pin down with any certainty in this period.

Being of Scots origin, the planters and settlers around Markethill were Presbyterian by conviction but worshipped at the Church of Ireland atop the hill of Mullabrack. In addition to establishing the structures of society, such as commerce and religion, the settlers could be called upon for collective defence. Archibald Acheson had stockpiled weapons in his bawn and in times of difficulty could muster one hundred and forty men to defend the settlement.

John Hamilton was granted 1,000 acres at Monela, now Hamiltonsbawn. By 1619 he had constructed his bawn measuring sixty-foot square and could muster thirty men from the twenty-six families settled on his land.

A condition of the plantation was that the native Irish be cleared from the land upon which the settlements were built. In theory these estates were to be self-contained bastions of English civility but, in practice, landowners discovered it to be more expedient to employ the native Irish in working the land. Landowners could not bring with them enough families to ensure efficient management of the land and so native Irish inhabitants were paid small sums of money to work the land they had once owned. If landowners could buy the labour of the Irish, they could not and did not quell the discontent in their hearts.

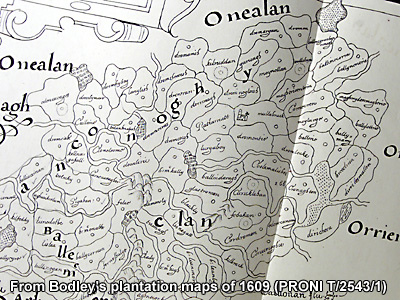

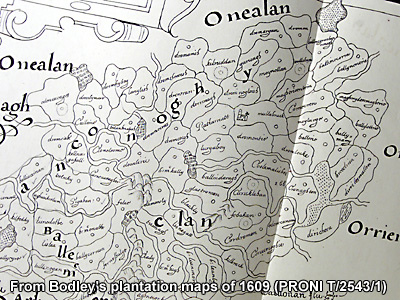

Read here about the production of the plantation map show above.